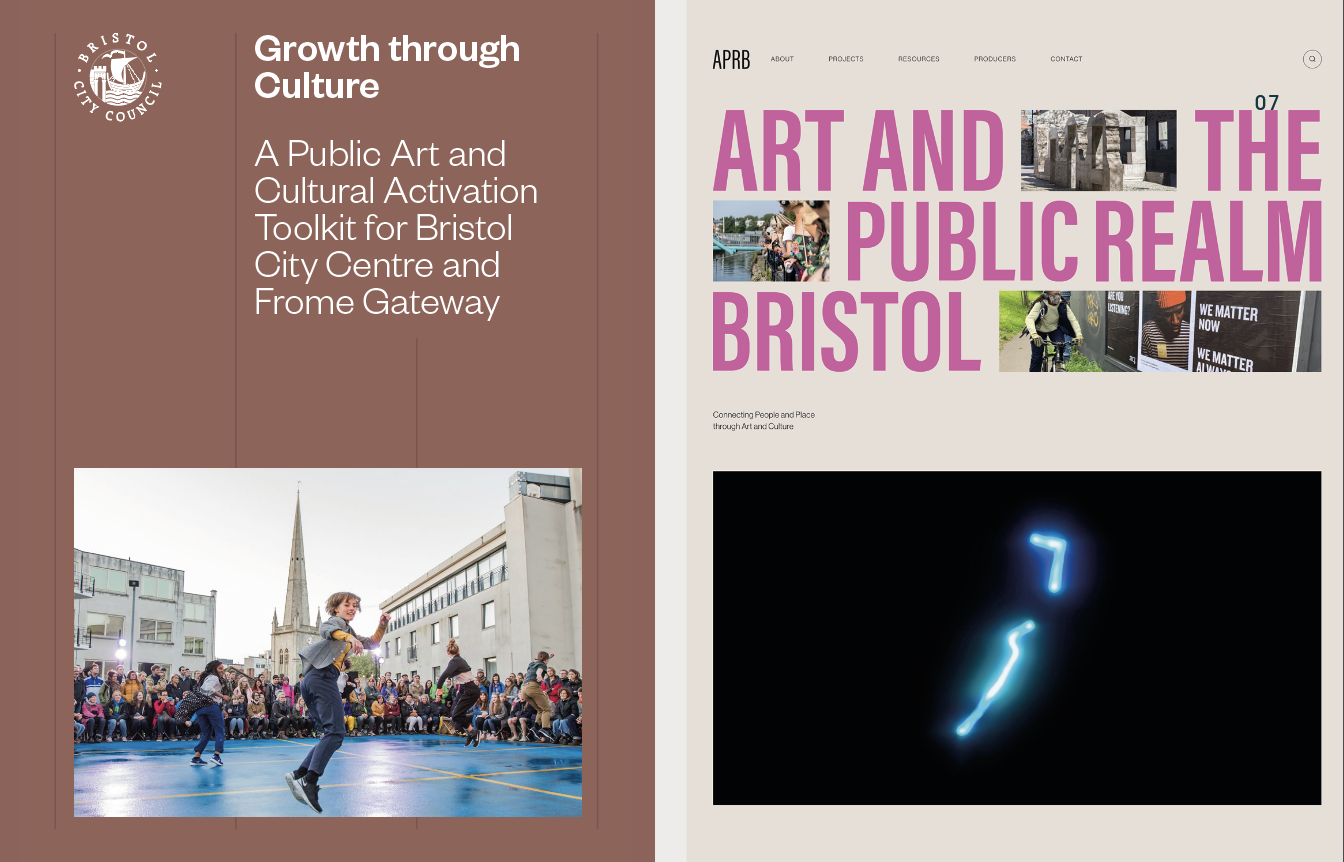

“Bristol’s Public Art Policy has enabled investment in over 150 public realm projects over the past 25 years,” she noted. “These projects are civic in nature - grown in response to people and place, shaping how citizens engage with the city.”

In cities undergoing change, culture is often treated as an afterthought - a soft layer applied once the big decisions have already been made. In Bristol, a different approach is emerging. Here, culture is not being added to the city; it is being woven into its foundations.

Across the city centre, a series of recent projects reveal how arts, memory, policy and design are being used not to decorate regeneration, but to shape it. What is emerging is a form of placemaking that understands culture as infrastructure - something that gives places meaning, resilience and long-term relevance.

These ideas came into focus through a series of walking conversations in central Bristol, convened by Place Collective UK, bringing together artists, creative producers, architects, policymakers and city-makers. Moving between cultural landmarks, streets and public spaces, those conversations revealed how Bristol is reshaping not just what the city looks like, but who it is for - and how it feels to live in.

A City Built on Making

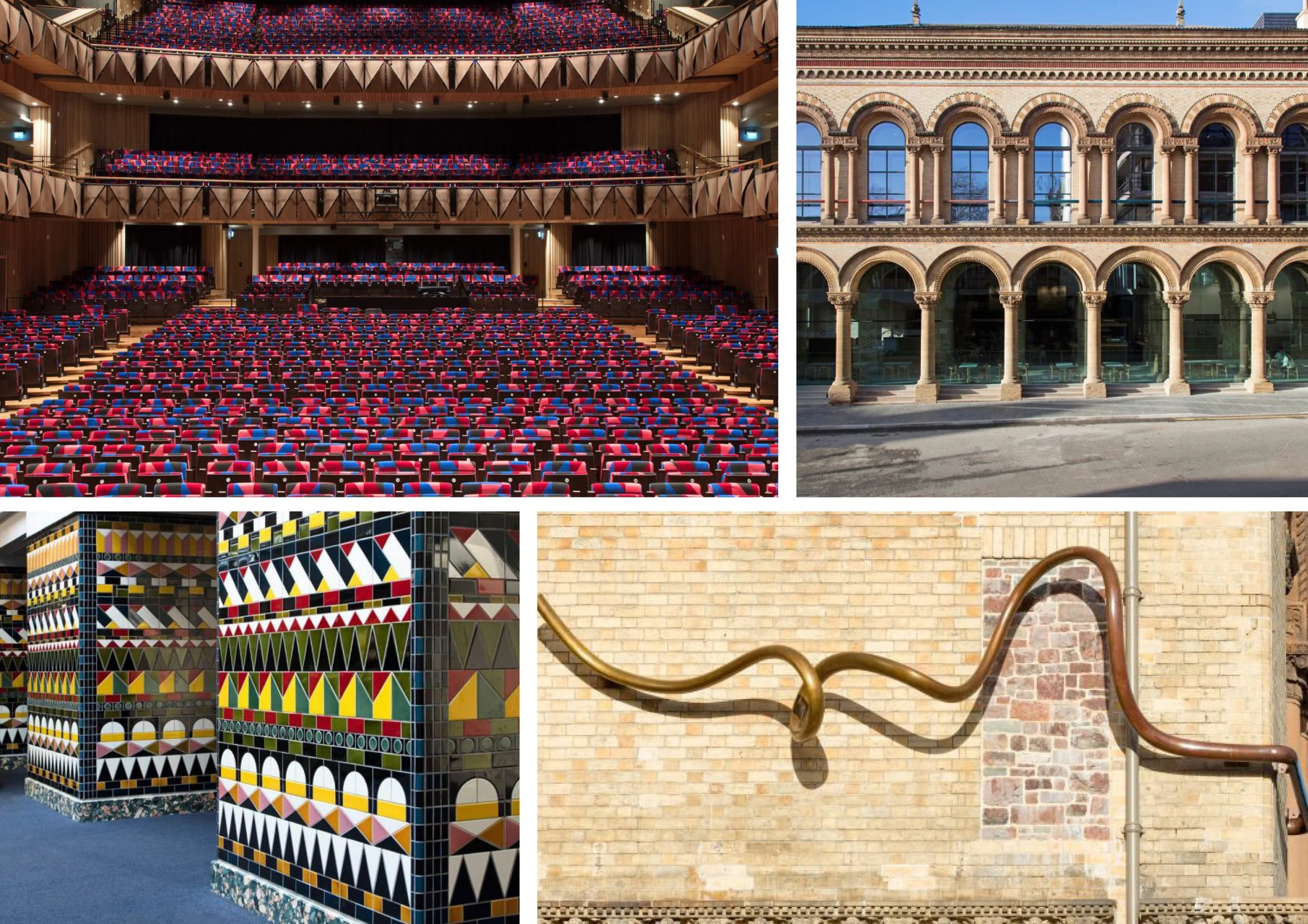

At the Bristol Beacon, recently reopened following a major transformation, culture is embedded directly into the fabric of the building. Theresa Bergne of Field Art Projects, curator of the public art programme, described how artists were involved from the outset of the design process.

“The artworks translate the craft of music-making into visual form,” she explained, “while reflecting Bristol’s spirit of ingenuity - its heritage of trade, making, and its contemporary creative scene.” Works by Linda Brothwell, Rana Begum, Giles Round and Libita Sibungu are not decorative gestures, but spatial anchors that shape how the building is experienced.

Georgina Bolton of Bristol City Council placed this approach within a longer civic trajectory. Here, culture operates as a form of continuity, linking past, present and future through both policy and design.

Our Common Ground, Oshii, 2025. Photo Courtesy Plaster Communications

Artwork by Rana Begum, Linda Brothwell, Giles Round and Libita Sibunga, Phototgraphs by Jamie Woodley

From Memory to Imagination

“It’s about honesty and imagination,” Oshii explained. “Facing the past while dreaming of a shared future. I wanted to create something that belongs to Bristol - a place where voices, cultures and histories meet on common ground.”

Elsewhere in the city centre, Bristol’s approach to contested heritage reveals a similar commitment to complexity over erasure. At the former Colston plinth, Historic Environment Officer Peter Insole reflected on the site’s evolving role — from the statue’s toppling in 2020, to its relocation to M Shed, and the installation of a new plaque that acknowledges the layered history of the place.

Rather than clearing the site of meaning, the city has chosen to contextualise it - allowing public space to hold memory, dialogue and learning. It is an approach that recognises cities as living archives, shaped by change rather than frozen in time.

Nearby at Centre Promenade, this reflective stance turns into proposition. Artist Oshii’s Our Common Ground, a floor-based artwork commissioned by Bristol City Council and Bristol City Centre BID and curated by the Bristol Legacy Foundation, sits within a wider reparative framework. Introduced by Tabitha Clayson from the Council’s Arts Development team, the project responds to initiatives such as Project T.R.U.T.H and the Colston What Next? process.

PCUK Bristol Walking Tour at Colston Plinth

PCUK Bristol Walking Tour at Common Ground

Reimagining Quakers Friars

“Culture here isn’t an add-on. It’s the foundation of the project, shaping what this place is, how it works, and who it’s for.”

At Quakers Friars, culture is being used not as a temporary activation, but as the organising principle of long-term change. Working with Hammerson, MOOWD is helping to reframe this historic site — once a 13th-century friary, later a marketplace and then a retail destination - as a new civic and cultural anchor within the city.

The approach is deliberately layered. Internally, buildings are being reimagined for cultural and community uses. Externally, the public realm is designed to support everyday life: performance, play, nature and informal gathering. Philadelphia Street is being retrofitted to accommodate diverse ground-floor uses, while integrated artworks reinforce the area’s evolving identity.

This thinking aligns with Bristol City Council’s City Centre Development and Delivery Plan and the Growth Through Culture Toolkit, both of which support the transition away from mono-functional retail towards mixed, creative neighbourhoods. Crucially, it is supported by emerging models of stewardship. As Mary-Helen Young of Ideas for Night and Day explained, new Local Plan policy will require 10% of ground-floor space in developments to be allocated to affordable cultural and community uses, underpinned by socially oriented property management.

Here, culture is treated not as event programming, but as long-term civic infrastructure - requiring care, governance and continuity.

Visualisation of Quakers Friars. Image Credit Hammerson and MOOWD

Growth Through the Cultural Toolkit and Art and the Public Realm Bristol website. Credit Bristol City Council

Opening Civic Institutions to the City

“This wasn’t just about improving performance space,” he said. “It was about civic accessibility - making the building porous, visible and welcoming.”

At Bristol Old Vic, the city’s oldest continuously working theatre, adaptive reuse demonstrates how heritage can be both preserved and transformed. A major redevelopment by Haworth Tompkins has reconfigured the building to be more open, accessible and visible within the public realm.

David Harraway from Bristol Old Vic described the significance of replacing a previously closed Georgian frontage with a transparent, street-facing foyer. “This wasn’t just about improving performance space,” he said. “It was about civic accessibility - making the building porous, visible and welcoming.”

The project illustrates how cultural institutions can extend their role beyond programmed events, becoming part of everyday urban life through openness, adaptability and generosity of space.

Interior of Bristol Old Vic designed by Haworth Tompkins

PCUK Bristol Walking Tour at the Bristol Old Vic

Culture as Civic Infrastructure

Taken together, these projects reveal a city working with culture as a system - supported by policy, shaped through design, and sustained by long-term stewardship. Rather than treating culture as a temporary layer, Bristol is embedding it within development frameworks, public space, property models and institutional change.

Culture, in this sense, is not a luxury. It is how cities remember, adapt and imagine themselves. It is how public space becomes meaningful, inclusive and resilient over time.

For MOOWD, this approach reflects a wider belief: that places thrive when culture is treated with care - not as spectacle, but as structure. Designing in this way requires patience, independence and a willingness to work across systems rather than symbols. In Bristol, that work is already underway - quietly, collectively, and with intent.